Indice dei contenuti

Planning a Year of Functional Training: Why It’s Essential

Planning a year of training doesn’t mean caging yourself in a rigid table, but building a clear direction that helps you improve consistently. In functional training, this need is even more evident because, along the same path, different physical abilities coexist: strength, endurance, power, coordination, mobility, and effort tolerance. Without an annual structure, it is easy to go from periods of enthusiasm to periods of stagnation, accumulating fatigue without real progress, or to alternate weeks “too light” with weeks “too heavy” that increase the risk of inflammation and minor injuries. Well-crafted planning allows you to deploy loads and recovery intelligently, creating measurable and sustainable progress.

Another important benefit is managing motivation: having a path with intermediate goals, deadlines and tests helps you perceive improvements and not lose momentum. Additionally, programming in stages allows you to maintain the qualities you’ve already achieved while developing others, instead of starting from scratch every time. Finally, planning helps you exploit the equipment strategically: it’s not just a matter of “doing exercises”, but of choosing tools and modalities that, at that time of year, produce the desired adaptation. Basically, a well-organized year makes you train better, not just better, and reduces the randomness that often limits results.

Goal Setting: The Starting Point

Any effective planning comes from clear objectives. “I want to improve” it’s not a goal: it’s a desire. A useful goal must be measurable and linked to training behavior. In functional training, goals may include strength (increasing loads in basic movements), metabolic capacity (improving endurance on prolonged or intense work), body composition (reducing fat mass or increasing lean mass), overall performance (better managing complex workouts), or health and longevity (moving better, with less pain and more control). The key is to choose 1 or 2 main goals and turn them into concrete indicators: loads, times, repetitions, heart rates, or standardized tests.

An often underestimated point is the hierarchy of goals: you can’t push everything to the max in the same period without paying a price in recovery and quality. It is more effective to establish what is a priority and what should be maintained. For example, if your primary focus is strength in the first trimester, you’ll need to maintain conditioning with minimal but consistent doses, avoiding chasing grueling workouts every week that drain energy and slow progression on loads. If, on the other hand, the goal is to improve metabolic capacity, then strength will become a “maintenance pillar” with targeted and relatively short sessions. This clarity allows you to choose consistent workouts, avoid contradictions, and truly measure progress, because you know exactly what you’re trying to move forward and what metrics to judge the outcome by.

Annual Periodization: How to Divide the Year

Periodization is the structure that organizes the year into phases, each with a central objective. In a functional context, where multiple physical qualities combine, periodization serves to avoid chaos and ensure that improvements are cumulative. A simple and very effective model includes macro-phases such as: base/reconstruction, development, intensification and consolidation/regeneration. This does not mean that each week will be identical, but that the overall emphasis of the period will be consistent. In this way, the sessions are not “feeling” choices, but respond to a logic: build foundations, increase capacity, push intensity and then recover to consolidate.

Dividing the year into phases also allows you to better manage real life: periods of intense work, holidays, routine changes, travel. Smart annual scheduling doesn’t pretend every month is the same; instead, it anticipates critical moments and inserts offloading weeks or lighter cycles where needed. Additionally, periodization makes it easier to monitor your body’s signals: if you begin to lose sleep quality, increase joint pain, or decline performance during a developmental stage, you have tools to intervene (reduce volume, change density, and insert recovery) without throwing away the entire process. In short, periodization is not “complication”, but a practical system that makes training more predictable, sustainable, and, above all, repeatable year after year.

Phase 1: reconstruction and baseline (8–12 weeks)

The basic stage is when the technical and physical foundations are built. Here the main goal is not “to split”, but to move better and create work skills without accumulating excessive stress. It is the ideal phase to take care of fundamental movement technique, control progressions, improve mobility and stability, and rebuild aerobic capacity. A common mistake is to skip this stage because it feels less “adrenaline-filled”. In fact, it is precisely this phase that determines how far you can go further, when the intensity increases. If the body does not have a solid foundation, the intense phase becomes a lottery between stalemate and injuries.

In practice, it pays to work with moderate loads, manageable volumes and a lot of executive quality during the base. Sessions may include technical work on squats, hinges, presses, and pulls, ancillary exercises to reinforce weaknesses, and intensity-controlled cardio sessions to build “motor”. The choice of workouts must also be made carefully: repeatable sessions are better, allowing improvements to be measured, rather than random variations every day. If you coach a group, this stage is perfect for aligning levels and standards, reducing technical differences that, later on, would become problems. It is a phase that gives less immediate results in aesthetic terms, but enormous in terms of performance and continuity.

Phase 2: development (10–14 weeks)

The development phase is where the bulk of the improvement is built. Here, volume and/or loads progressively increase, and force and conditioning begin to be combined in a more structured way. The goal is to expand capabilities: more strength in basic movements, greater work tolerance, better efficiency in cyclical movements and mixed workouts. The key word is progressivity: small but steady increases, without chasing weekly peaks. At this stage, you can work with well-defined progression patterns, such as load increases every 1–2 weeks, or volume increases while maintaining impeccable technique.

From a practical standpoint, development requires managing recovery: if you push too hard, you burn continuity; if you push too little, you don’t create adaptation. For this reason, it is useful to alternate weeks of loading and weeks of relative unloading, or to insert micro-cycles that modulate the intensity. Conditioning also needs to be planned: spaced jobs, different domain time, sessions focused on specific capabilities. The goal is not to always do the best, but to improve efficiency and the ability to sustain increasingly greater intensities. In a gym or box, this stage is perfect for introducing periodic (simple and repeatable) benchmarks that help athletes and clients see real progress, increasing loyalty and motivation.

Phase 3: intensification (8–10 weeks)

The intensification phase is the period when the bar is raised. Typically it decreases the total volume a little’ and increases the intensity: higher loads, denser jobs, shorter but sharper “sharper” workouts. The goal is to transform foundation and development into performance: greater power, the ability to push hard, and better fatigue management in high-intensity settings. It’s an effective, yet delicate phase: it requires listening to the body, attention to technique, and careful recovery. Here it is not advisable to accumulate stress “randomly”, because fatigue can become systemic and impact sleep, appetite and performance.

To manage intensification well, it is useful to choose a few indicators to push on and leave the rest in maintenance. For example, you can aim to improve one main lift (or two) and one or two metabolic domains, without wanting to excel on everything at once. The selection of exercises is also important: complex, high-risk movements should be included carefully and only if the technique is stable. Intensification is not the time to “learn from scratch” difficult technical gestures, but to express what you have consolidated. At this stage, offloading weeks become even more essential: if you skip them, you risk reaching the mid-cycle already offloaded mentally and physically, reducing the very intensity you want to build.

Phase 4: consolidation and regeneration (4–6 weeks)

After a period of intensity, the body needs to consolidate adaptations. The consolidation and regeneration phase serves to recover, maintain key qualities, and restore energy, mobility, and movement quality. It is not a “empty” phase: it is a strategic phase. Without regeneration, many athletes enter a loop of chronic fatigue: mediocre workouts, recurring pain, and waning motivation. With a well-designed phase, however, you arrive at the next cycle fresher and ready to start again with a new improvement block.

In practice, at this stage the overall volume is reduced and quality is taken care of: technical work, one-sided accessories, control exercises, light aerobic sessions and mobility/stability work. It’s a great time to do a postural and movement “check”, review mistakes, and reinforce weaknesses. You can enter light tests and compare the results to the beginning of the year to measure improvements without excessive stress. For gym owners, this phase can coincide with periods of lower attendance or a change in scheduling, giving customers a feeling of “reset” and preventing dropouts due to fatigue or overload.

Progressions: How to Improve Without Stopping

Progression is the engine of improvement: if the stimulus does not grow over time (or change intelligently), the body has no reason to adapt. In functional training, progression isn’t just about increasing weights, it can happen in multiple ways: load, volume, density (same work in less time), technical complexity, movement control, and recovery ability. The choice of progression depends on the time of year and the goal. During the base, for example, it is useful to progress especially on technique and controlled volume; during development, load and volume increase; during intensification, density and intensity increase.

A key principle is to avoid drastic jumps: small but steady progressions hit occasional peaks followed by stops. To achieve this, it pays to work with cycles that involve weeks of loading and weeks of unloading, or models in which the intensity gradually rises and then you “breathe” to recover. Additionally, it is important to choose monitoring metrics: loads on fundamentals, time over standard distances, repetitions in a defined time, or perception of effort. The best progressions are the ones you can measure and replicate. If everything changes every week, it becomes difficult to understand what is really getting better. Consistency, rather than variety for variety’s sake, is what makes a year of real growth possible.

The role of equipment in annual planning

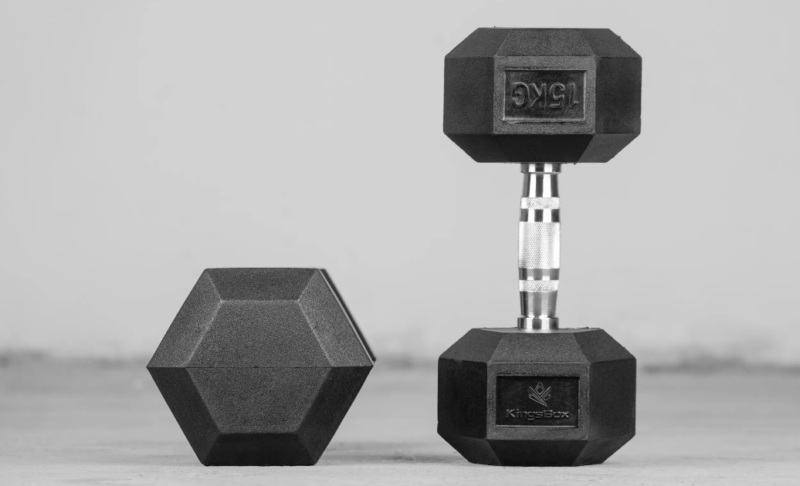

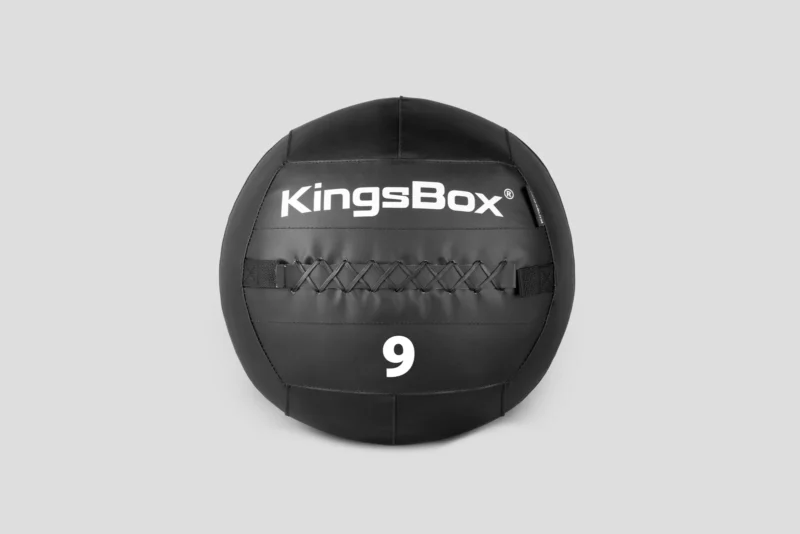

The equipment is not a simple “outline”, but a tool that determines what stimuli you can apply and how. Planning a year also means deciding when to use certain equipment to achieve precise adjustments. In the basic stage, for example, tools such as barbells, racks, discs, and kettlebells are ideal for building strength and control. In the development phase, introducing variables such as dumbbells, wall balls, sleds, and boxes increases the variety of stimuli without losing structure. In intensification, tools that allow for high density and power (such as sandbags, slam balls, rowers, or bikes) help safely push intensity because they modulate joint stress and allow for measurable work on metabolic capacity.

From a practical point of view, the choice of equipment must follow the logic of the programme, not the impulse of the moment. If the focus of the quarter is strength, the primary equipment should support progressions on fundamentals; “metabolic” tools come in as a dosed complement. If, on the other hand, the focus is aerobic capacity and resilience, the equipment that allows for prolonged and controllable work becomes central. Real availability also matters: in a home gym, you could build a very effective year with a few well-chosen elements; in a gym, a larger endowment allows you to manage different groups and levels. In any case, using the equipment on an annual basis means avoiding redundancies and maximizing results: each tool enters the program because it serves a purpose, not because “it makes a scene”.

What equipment to buy

Rower

Common errors in annual planning

Many programs fail not due to lack of effort, but due to setup errors. The first is to always train “full-time”, as if each session were a final: constant intensity without phases almost always leads to chronic fatigue, a decline in performance and injuries. Another mistake is not distinguishing between periods: if the whole year is the same, the body adapts and stops improving, or it accumulates stress without benefits. Ignoring off weeks is also a classic: offloading is not “wasting time”, but creating the conditions for the body to absorb the stimulus. Finally, vague or inconsistent goals make it impossible to evaluate the path: if you don’t know what you’re chasing, you’ll never know if you’re doing well.

A more subtle mistake is the haphazard use of functional training equipment and exercises: constantly changing because “so you don’t get bored” it can sabotage progressions. Variety is useful, but it must serve the goal. Furthermore, neglecting mobility, stability and technique often presents the own account in the intensification phase, when loads and density increase. Managing recovery outside the gym is also part of planning: sleep, nutrition, and stress influence adjustment as much as sets and reps. A well-built year is not one in which you do more and more, but one in which you do the right things at the right time, with room to recover and continue to improve without interruption.

Conclusion: Train better, not just better

Planning a year of functional training means building a path with direction and method. It means setting measurable goals, distributing the year in coherent phases, applying intelligent progressions, and using equipment strategically. This approach makes training more sustainable and allows you to achieve more solid results: strength that grows without recurring pain, endurance that improves without destroying recovery, and overall performance that becomes more stable. When programming is done well, motivation also increases, because the body responds and progress becomes visible and measurable.

The real advantage of annual planning is continuity: you don’t depend on the mood of the day or the “perfect tab”, but on a system that accompanies you week after week. Each stage makes sense and prepares the next, avoiding the feeling of always starting over. If you want to make this journey even more effective, you can enter periodic tests, keep a training journal, and adjust the program based on real feedback (energy, sleep quality, pain, performance). A well-planned year is not a rigid plan, it is an adaptable strategy. And when you learn to think like this, you can repeat this pattern over the years, progressively improving with less stress and more results.